Gentillesse: A Tour of Spitalfields With The Gentle Author

- ArtsySuzie

- Jan 5, 2022

- 7 min read

I haven’t really explored Spitalfields or East London before; thoroughly recommend a tour with the Gentle Author. Be prepared for interaction, knowledge and storytelling: go with an open heart and mind. You too could learn about the wonderful stories of a resilient community overcoming the violence experienced within and without; the layers of history and its ongoing vibrancy today.

Not sure who the Gentle Author is — well you really should, I commend their blog to you here, with more stories of Spitalfields life past and present — https://spitalfieldslife.com/

Please note the following thought are entirely my own and nothing to do with the Gentle Author or the wonderful Spitalfields Life blog, only I started to think as I saw the East End with new eyes.

As I went around with the group, I started thinking again about this article — https://stoneageherbalist.substack.com/p/midwinter-melancholia?justPublished=true

Without meaning to be rude, I think I’ve read a completely different article to many others. Much of it horrified me. In highlighting the love of the ‘English aesthetic’ for all things old, rural, gloomy, accumulated and dusty, it highlights a certain type of classicism — Downton Abbey chic and snobbery against IKEA and posher versions such as Oka, not to mention rural over urban and well a dislike of modern life.

When the Gentle Author talked about some wonderful saved 18th century town houses, some stories from the 1940s residents of the street were read to us. Rather than admiring “the twilight and the gloom…[summoning] the need for heavy curtains, stone floors, old wood polished by time”, the 1940s residents were glad to leave these old, dirty, unfit for family homes to move to modern houses (probably with electricity, easy to clean facilities, fully plumbed indoor bathrooms and toilets, and lifts or steps rather than crossing roof tops to literally drop in on their neighbours; gas and electricity straight from a switch or dial; or maybe even homes with actual gardens and green playing fields, multiple bedrooms, proper indoor bathrooms and flushable, inside toilets). Without disparaging the playing in the streets or community culture, I’m not sure that previous generations were finding that “Glass, steel and concrete are too harsh, too flat and visible”.

Where has this anti-modernism come from, that village life is the best life, that ancient is perfection? That old naturally equals best and ‘Anglo’? Whilst there may be ongoing and concerning issues such as the blocking of light by tall commercial buildings, the unnecessary ‘clearing’ of Spitalfields communities and businesses to build hideous facades and empty tall buildings rendered no longer lucrative in their space maximisation by the ongoing Pandemic and working from home; the heinous lack of upkeep and use of poor materials of the concrete cities in the skies, I’m not sure that our ancestors felt so strongly that “the English imagination is truly refreshed is seeing the tiny cubbyholes and niches in an old house, the crooked little table in a corner, in the piles of old books and the dusty travel trunks on top of the wardrobe.”….And it also raises a bigger question — why are urban communities (especially the economically disadvantaged) so often poorly served in terms of services, resources, access to facilities and even in the places they live in —’ cleared’; ripped off such as in Grenfell ‘maintenance’ or uncared for, in many blocks, which are redeveloped as luxury flats. Even though the communities have their own ideas about how to live and are vibrant… Why aren’t communities being listened to?

My own Grandad was a farm labourer in a rented cottage, tied to the job. How romantically gloomy and dusty I hear you sigh. But we weren’t converted barn owners. It wasn’t — they didn’t - get full plumbed in and electrified until the 1950s — the toilet for many years was a dark cupboard or shed at the bottom of the garden; I don’t know if they knew the convenience of fridges, easy clean worktops or light everywhere at the flick of a switch and an energy saving bulb at this time. It seems to me that this longing for dust and dirt is not only at odds with our COVID times of sterile and hygienic, virus-zapping environments, but very classicist in many ways. In the 1930s, many Tudorbethan fakes were built in suburbs all over the place, chasing a rural past that never was; the same after World War One when traumatised soldiers were encouraged to reconnect with themselves through Morris dancing; goodness even in Elizabethan times, they were hankering for Elysian fields and pastorals, capering nymphs and shepherds, not to mention the later Paradise Lost and Arcadia regained.

But is it and was it, Paradise lost? Thomas Hardy says not. And I wonder why were are so hard and unloving on urban environments. Far from the “cosy glow of the pub and the tavern”, 19th century pubs were often gaudy palaces, agog with gold, gilt and bling, and so many flashing tiles of colour. The mega Tudorbethan pubs were built to accommodate cyclists and then motoring daytrippers. Again, this eulogised retreat sounds like a country pub, many of which are under serious threat from COVID and second home owners at the moment as rural community hubs close and founder, due to lack of investment in modern local facilities for all.

I don’t disagree with the article’s author on time though — I saw wonderful layers of history to be proud of in Spitalfields; the outline of an Henry VIII destroyed abbey in a car park — the hospital for the unwanted sick on the outskirts of the city giving the area its name; the French Huguenot refugee houses; the Jewish synagogue; the Bangladeshi owned textile factories and homes; now Afghan communities making their mark too. And yet, I’m glad that time has moved on — that the Brewery no longer demarcates between the racists and the community they loathe; that the community fought back against racism; that students squatted to protect an unloved 18th century townhouse from demolition, enabling me and my tour group to travel back in time so wonderfully.

In addition, I would argue that the Anglo aesthetic is not so much time as walls. Given half a chance, some of us love to barricade ourselves between four walls, fences, front doors, garden gates; to separate. The Pandemic has brutally highlighted the privilege between those who can barricade and work from home and access a private garden, and those who can not.

“Modern Britain seems to crave shiny flat new buildings, smooth driveways, minimalist interior design, open plan office spaces, glass fronted public libraries and screens to direct, inform and guide at every turn of the head. We have abandoned the much older love for the ancient as part of the quieter rhythms of the year, and in its place a rush to the two-dimensional and the surface.”

And what is wrong with modern shiny things? The Gherkin, Walky Talky and perhaps the Tulip to come are fantastic and fun buildings; who cannot love the Sky Garden? More worrying should be the destruction (such as by own city’s council) of perfectly reusable older industrial buildings (promoted by wider government policy which makes refurbishment prohibitive, and promotes the creation of mocking facades using the skeletons of existing older buildings.

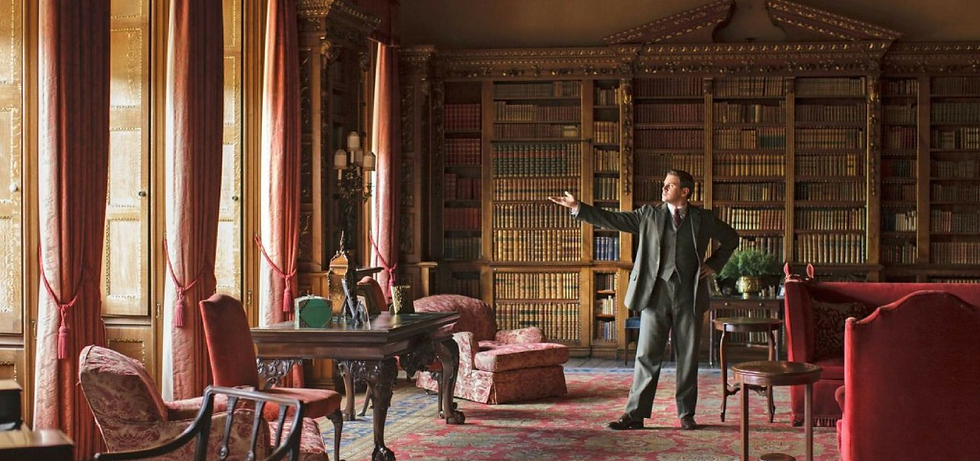

Aghast at the snobbery and classism here, the rejection of minimalism over and against dirt, dark, gloom and clutter, I wonder if this is why I love to run to a National Trust or English Heritage property, enjoy the clutter of others “rejection of the minimal and neat aesthetic, a preference for clutter, casually thrown blankets, a mismatch of Oriental rugs and stags heads, a need for multiple levels of height in decoration, with no obvious guides”, and then dash back against to my glorious streamlined Ikea minimalisism, channelling 1970s chic. Calke Abbey for me is a premier example of this — I enjoy the frozen in timeness of others hoardings and then go back to purge my own!

The author of the article, I think, overlooks the democraticing of Ikea and others like them; even the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge are alleged to have Ikea bedroom furniture for their children. And it’s not just Ikea, Habitat and others aimed to promote awareness of modern design and aesthetics at affordable prices for all. The anthesis of “The feeling evoked is one of timeless occupancy, with each generation merely adding, modifying and jumbling”…..

In conclusion, the author reveals their compulsion to “Everything that is older than 1945…. I get the impulse to grind it all away into dust and obliterate the very memory of the stones”. This scared me, not only the focus on a certain type of ‘Englishness’, the anti-urbanism, the reverence of the old over the new world we live in now, but most deeply the obliteration of everything older than 1945. Whose 1945 are we talking about here? When would we stop the clock? Have we won the war, remain in it, dropped the bomb, or are we in post-war austerity, which is when a lot of the concrete and shiny metal horrors so decried by the author began, in the rush to create homes fit for heroes amidst a shortage of money, materials and perhaps long-term vision — not to mention a simple desperate need for homes, for safe shelter. Heartfelt too was the desire to improve on the old and irrelevant dirty, unfit dwellings of before; although the outworking of this vision may have been imposed rather than thoughtfully considered, abandoning the higher ideals of Le Corbusier which included facilities and high quality materials.

Are we really saying that life was better pre-1945?

Pre-1945, it is worth reflecting that Tudor and Elizabethan, British Classicism, Neo-Classicism, Rococo, Art Deco, Arts and Crafts, Victorian Gothic and more were all despised in their day as arbiters of the ‘new’. Neo-Classicism despoiled Tudor style; the Victorians knocked down Stuart and Elizabethan homes to build railways and grandiose civic buildings and commercial empire, often without caring for the communities they carved through (the High Speed Rail of its day); in the 1930s, the magnificent town houses of the 18th century were obliterated, stucco by stucco, to build Art Deco apartment blocks and offices.

In conclusion, given that every generation can be accused of cultural and social vandalism, whose voice and whose heritage are we giving precedence to? Why are we valuing some communities over others and perhaps putting the past under a somewhat nostalgic gaze of white, pipe smoking men tramping across the wind- and rain- lashed moors and heather? This sounds not unlike Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and their tartan mania at Balmoral — creating a Scotland that never was and in so admiring all things Scottish, that they sought to outdo all Scottish traditions in a glorious and somewhat tasteless colourful muddle, (with extra stags heads thrown in).

More importantly, why are urban and indeed rural communities being so horribly neglected today, in terms of health and safety, facilities, resources, justice? As some of us seek to admire dust, gloom and the old, we would do well to see who and what lies beneath , whose labour built it, at what cost and what is happening to the communities, the people there now — Bristol and other big commercial cities and former industrial towns being key examples.

Comments